Loose thread III

Explorations of bird making practices and relay production.

Wool, straw, great tit

As signs of spring began to show in the garden I noticed an abundance of birds.

Starlings were once again flitting from the fence to the un-mowed lawn, bobbing through the blades in their search for bugs. House sparrows could be spotted clinging to the brick wall of my neighbour’s garage, and the red breasted robin began gathering twigs and spider silk to make a nest.

This sight brought be back to the spider on my mesh sculpture, spinning its web within the void. I once again began to consider the existing making practices of birds and wondered if it might be possible to collaborate in their making practices as well as entice them to collaborate in mine.

I began to research the nest building practices of birds, what materials they use, what forms they make, how they strengthen and structure their creations. In the course of this research, I became aware that my choice of material would be key to this interaction, not only from the point of view of appealing to the birds but also from an ethical standpoint.

Increasingly, birds living close to humans are using manmade materials in their nest building. It is not uncommon to find plastics, twines, strips of fabric and even coat hangers and barbed wire in bird nests. It is assumed that these choices are being made due to the relative lack of natural nesting materials, however in some instances birds appear to actively choose manmade building materials for reasons apparently beyond them just standing in for more traditional nest fodder.

It has been suggested that certain anthropogenic materials may have beneficial effects within bird nests. For example, a study conducted in Mexico City found that nicotine in cigarette butts, which are often found in urban bird nests, may be beneficial in keeping nest parasites at bay.

The extent to which this is effective or actively chosen by birds is not conclusive however it seemed that birds were choosing smoked cigarette butts over unsmoked ones, and the parasite repelling properties were only found in smoked cigarette butts.

The researchers suggested that the birds could distinguish smoked and non-smoked butts from their scent, which may have been similar to other compounds they recognised as having parasite repelling properties.

Studies such as this are helping us to understand the possibility that animals may seek out manmade materials over natural materials where they may provide benefits. There is also an argument that aesthetic preferences play a part in nest material choices, and that an abundance of colour and texture that may be less easily found in nature affects choices made by the birds.

When considering what materials I would use in my collaboration attempts, I was conscious that although birds may use anthropogenic materials, these can also be extremely harmful. For example, plastic may be consumed by young birds, wire or twine may become wrapped around a bird and injure them, or coloured dyes and inks may leach out chemicals that may harm developing chicks. Items such as foil and plastic can also disrupt the normal temperature regulation of nests.

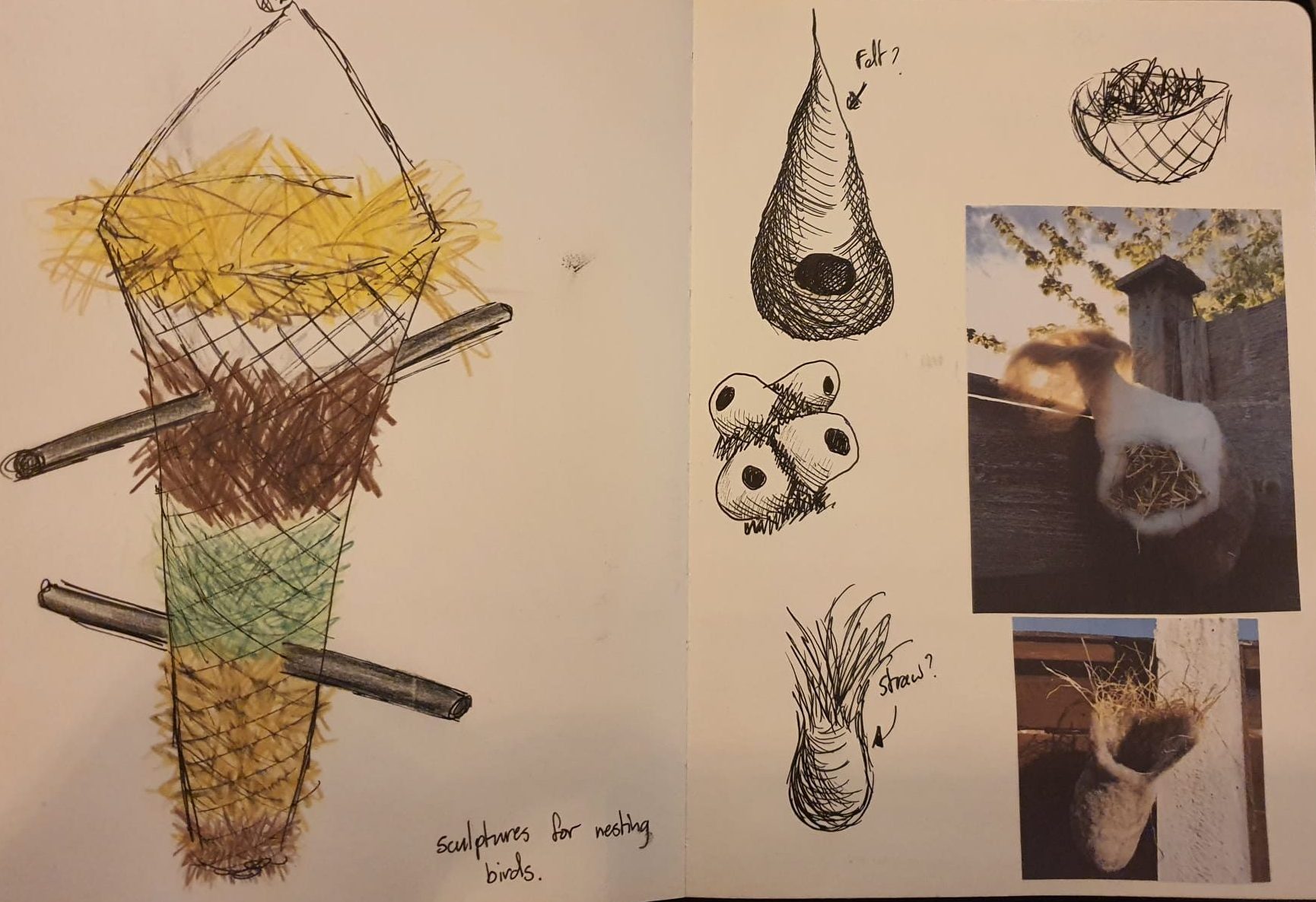

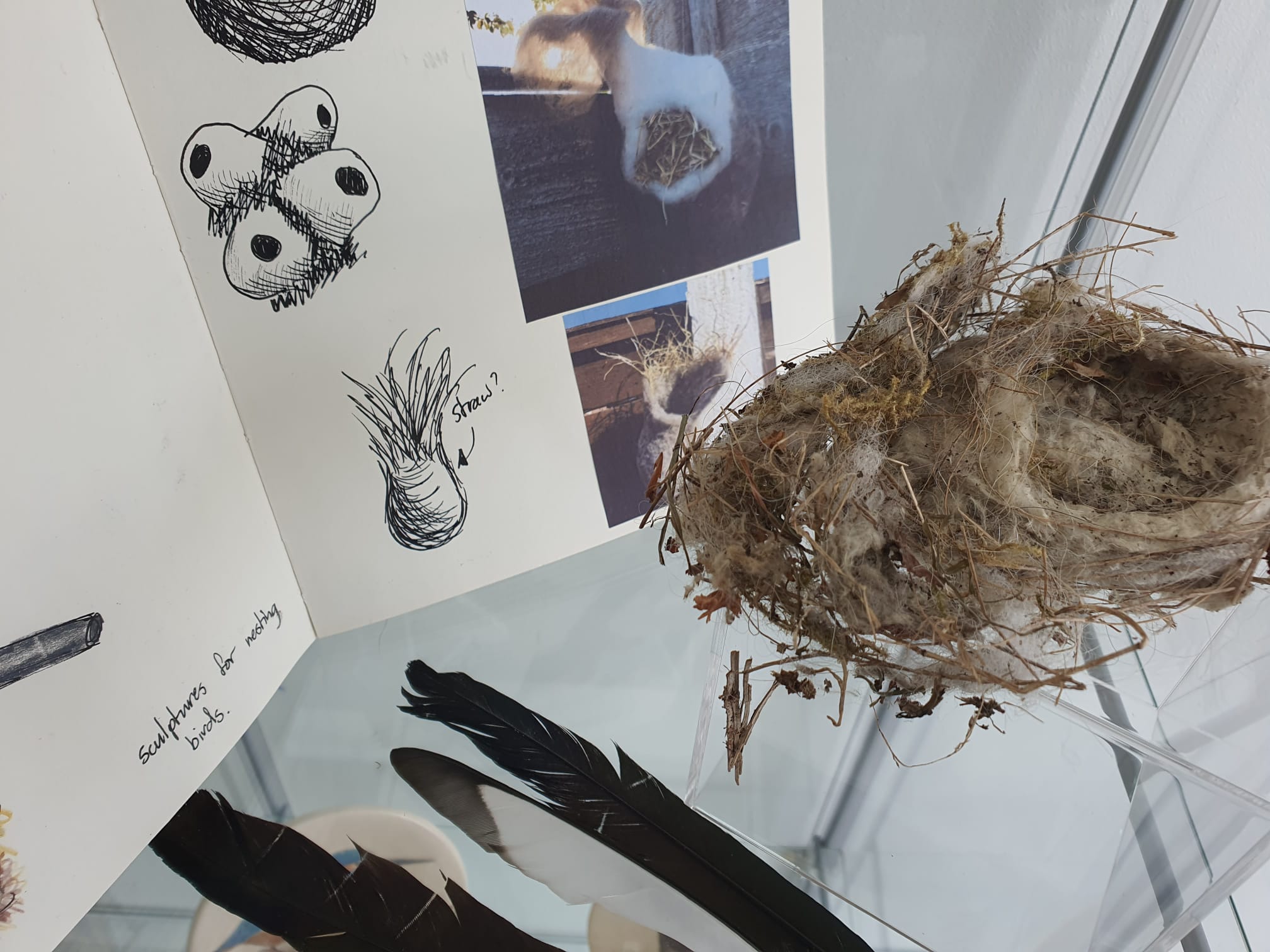

Wool is an interesting material when working in the realm of meshes and entanglements. It may be loose and fluffy, fibrous, twisted to thread and knitted into a fabric, or stiffened into a structure through felting. It is a material which is routinely utilised by birds in their nest building and one which is deeply embedded in considerations of human/non-human relationships throughout history. As such I chose wool as the material base for my next round of experiments with multispecies making.

The process of felting particularly appealed to me as the use of a needle as a stand in for a beak seemed to bring me towards a closer approximation of the birds’ dexterity and scale of movement in their own building practices. While not exact, it seemed that the needle could stand in for a beak, and the formation of the nest shape could be guided by the process of working with the wool and the tool.

The form that began to emerge reminded me of weaver bird nests, and although I had not consciously tried to recreate the tear drop shape of these birds’ homes, the pouch like form was a useful one as it allowed me to fill them with more loose hay. I began to wonder if the birds might adopt these forms as a nest rather than just take the materials from them.

Once complete, I hung the felted wool and hay structures in the garden where I thought the birds may feel safe enough to venture. It was not too long before curious birds began to investigate them. Just as with the apple sculptures, the birds’ interactions began to change the sculptures, albeit in subtle ways. The rim of unfelted wool I had left on one of the forms thinned and stretched as birds tugged away tufts, and as they began to pull the hay padding from the forms their shapes altered in in the wind.

It also seemed that the forms had shrunk slightly, although I cannot say definitively by how much as I didn’t measure them before placing them outside. Perhaps the combination of dampening from rain showers and morning dew, changes of temperature, or even the friction of the wind rocking them against the fence and brick caused the felting process to continue without my input.

This foray into nest making gave me time to reflect further on the making practices of other animals. We often think of aesthetic practice, building and art making as things which set us apart from other animals, however nonhuman making practices are not only well documented but may also reveal an aesthetic intelligence that rivals our own.